Introduction

Some time ago, the possibility was suggested to include a subject of Jewish literature in my artwork. Being enthusiastic, it was instantly obvious to me that the subject would have to be an element from the culture that was dominant in Spain before the Jews were expelled from that country in 1492. I appreciate Spanish medieval poetry and have also read some Arabic and Hebrew poetry from that time, but as a result of this project I started to try and gain more insight in this literature. I discovered a group of cabbalists that had formed themselves around Nachmanides in Gerona in the 13th century. From one of these writers, Meshullam ben Solomon Dapiera, I found a text that appealed to me. It is a “lyrical prelude” to an epistolary ode to Nachmanides. A prelude such as this is a well-known figure of speech in early Arabic and Hebrew poetry. It is a poem about the love of the poet for his mistress, like so many before that have been written in Andalusian court-poetry.

I have a maiden whom no man has ever known;she is my chief love and treasure

Her eyes brighten when she hears the bells and pomegranates on the hem of my cloak.

My faithful envoys, as if they were clothing merchants, brought her embroideries,

but they made no mention of payment,demanded no return for my wares.

How joyfully the messenger then informed me that she had accepted my garland of hennablossoms and lillies

and had sent me a necklace of Nubian gold. It is as dear to me as braided plates of gold and crescents.

In it I can see the carved figures of lovers, like the figures that are engraved in my imagination:

A beautiful woman, sleeping on the breast of her lover, and her face upon mine.

How precious were those days when the voices of graceful girls rang in our ears!

Those youthful days are gone, yet we greatly rejoice in the honour of old age.

My head is covered with a glorious turban of grey hairs, my beard is white.

Youth’s ornament has been removed, now the fear of sin hangs like a jewel from my neck.

If you find that my tributes are worthy with falsehood, know that they were written in jest and over wine.

When we poets extol the virtues of famous men to the sound of pipes, pay no heed:

ours is a labour of lies, and that is why my verses and my mouth are full of deceit.

It is in play that we celebrate the men of our time, and not to win the favour of listeners.

In truth, I only love the man whose face bespeaks his love for me, and he too will see love’s pledge in my eyes.

As for those whose love is suspect, for them I have a double heart; and I can weigh the suspicion in the balance.

In the first part the writer sings of his relationship

to his beloved when they were young. In the second part, however, he explains

the virtues of his grey hair, the wisdom that has grown in him and then, in a

satirical manner, he examines the responsibility and the attitude of the poet.

This second part was totally contrary to the convention in this kind of poetry

in which youth and beauty was the only thing that mattered.

To begin with, he recognises the love that he feels for his muse, his secret lover. He always surprises her with his numerous observations in exchange for which and through her inspiration, he creates many of his paintings. That love was an earlier subject of my work, refering to the troubadours of Provence, in France, who found greater value in the virtuous writing and singing of poems, honouring their love for a maiden, rather than in consumating that love . It is exactly the attitude of the poet which is a theme in the second part of “Of Love and Lies” that intrigues me. Dapiera first sings of earlier days and how much wiser he is now and then he describes the attitude that he came to as an artist. Ironically he enhances the flattery and sweet-talking of his collegues to their patrons, thus drawing a dividing line between them and the virtuous poet he himself strives to be. He will only be understood by listeners of similar attitude, forming with them a secret alliance, impalpable to outsiders.

The essence of this attitude is illustrated by a riddle-poem by Dapiera:

They asked me: “O wise one,

who is it that doesn’t distinguish good from bad

And sings in praise of the men of the time

Though his heart weighs the truth and ponders it?”

I answered them: “It is I, my friends, I am the lying poet!”

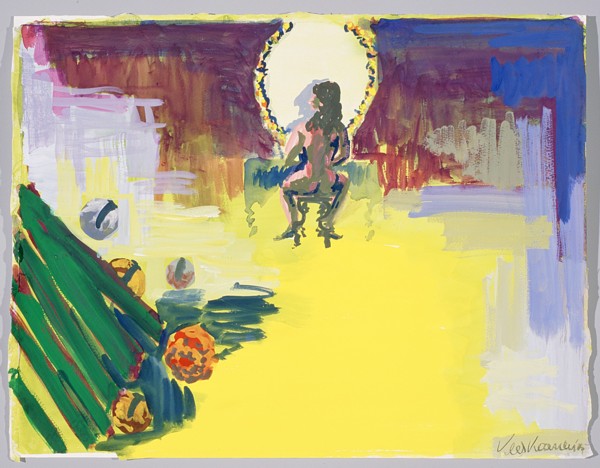

My unknown lover – 2006

My unknown lover – 2006

Gouache on paper – 50×65 cm

Her eyes brighten – 2006

Her eyes brighten – 2006

Gouache on paper – 50×65 cm

My garland of hennablossoms and lillies, her necklace – 2006

My garland of hennablossoms and lillies, her necklace – 2006

Gouache on paper -50×65 cm

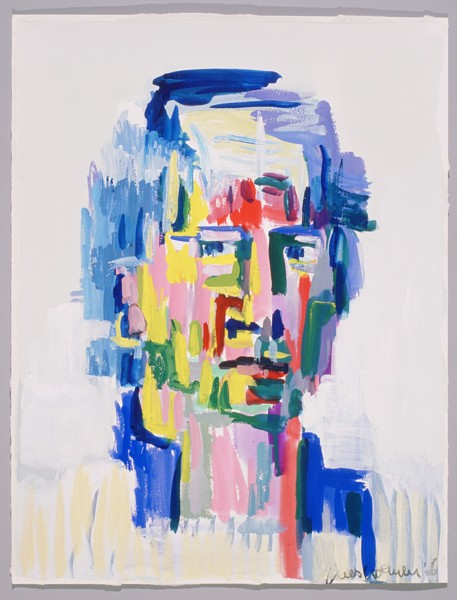

Engraved in my imagination – 2006

Engraved in my imagination – 2006

Gouache on paper – 50x65cm

Her face upon mine – 2006

Her face upon mine – 2006

Gouache and plastic tape on paper -50×65 cm

Those youthful days – 2006

Those youthful days – 2006

Gouache on paper – 65×50 cm

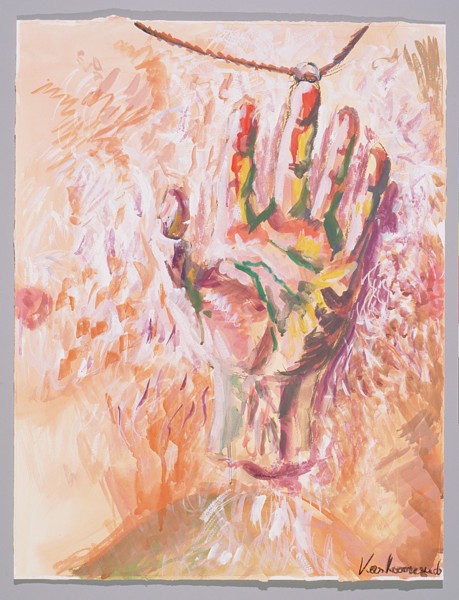

The fear of sin – 2006

The fear of sin – 2006

Gouache on paper – 65x50cm

In jest and over wine – 2006

In jest and over wine – 2006

Gouache on paper – 65×50 cm

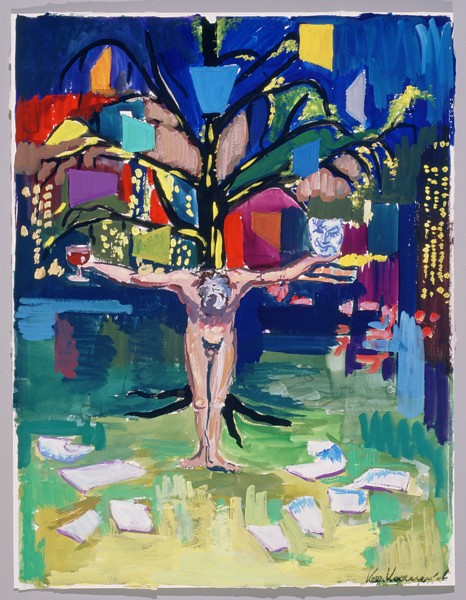

My verses and my mouth are full of deceit – 2006

My verses and my mouth are full of deceit – 2006

Gouache on paper – 50×65 cm

I can weigh suspicion in the balance

gouache on paper – 65×50 cm

The gouaches that I have painted as a result of this text contain images and techniques that I have used in different periods of my career as an artist. I made this choice to put more emphasis on the element of reflection during the course of my development.

Kees Koomen

The Hague, 25 February 2006

References:

Carmi, T. (1981) The Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse – Penguin Books, London

Brann, R. (1990) The Compunctious Poet: Cultural Ambiguity and Hebrew Poetry in Muslim Spain – John Hopkins University

Brill, E.J. & Silver, D.J. (1965) Maimonidean Criticism and the Maimonidean Controversy Leiden pp.1180-1240